The UK has always been at the forefront of innovation in financial services. From direct debits to Faster Payments to open banking, Britain has consistently led the way. Yet with stablecoins, it risks missing the moment.

Though often ridiculed, crypto has the potential to reshape the infrastructure of global capital markets. Britain is yet to capitalise on this technology — and the costs to the UK’s competitiveness could be severe.

Equally severe are the risks — central bankers warn that stablecoins simply aren’t money. Treating them as such, they argue, is dangerous and could risk financial stability.

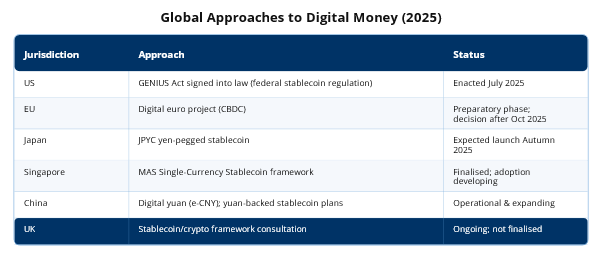

This debate has intensified following the passage of the Trump’s GENIUS Act, which set out the US’ legislative and regulatory framework for stablecoins. Industry has responded with encouragement. Even crypto-critic, Jamie Dimon has confirmed that JPMorgan will get involved, with Citigroup, Amazon and Walmart all planning to issue their own coins under the legislation. Now other jurisdictions are scrambling to keep pace.

With the rest of the world seemingly engaged in a crypto arms race, the UK’s response is notably more muted.

As debate escalates, the UK government will eventually have to answer the question, are stablecoins the future of financial services?

Stablecoins Explained: What They Are and Why They Matter

Stablecoins are a form of cryptocurrency designed to maintain a stable value — hence the name. This is achieved by pegging their value 1:1 to a fiat currency, most commonly the US dollar, or to a commodity such as gold.

Unlike non-backed crypto assets such as Bitcoin, which lack intrinsic value, and are typically treated as speculative investments, stablecoins are used more like currency: functioning as digital cash within crypto markets — a safe intermediary for trading and transferring value across exchanges — and increasingly as a settlement layer in decentralised finance.

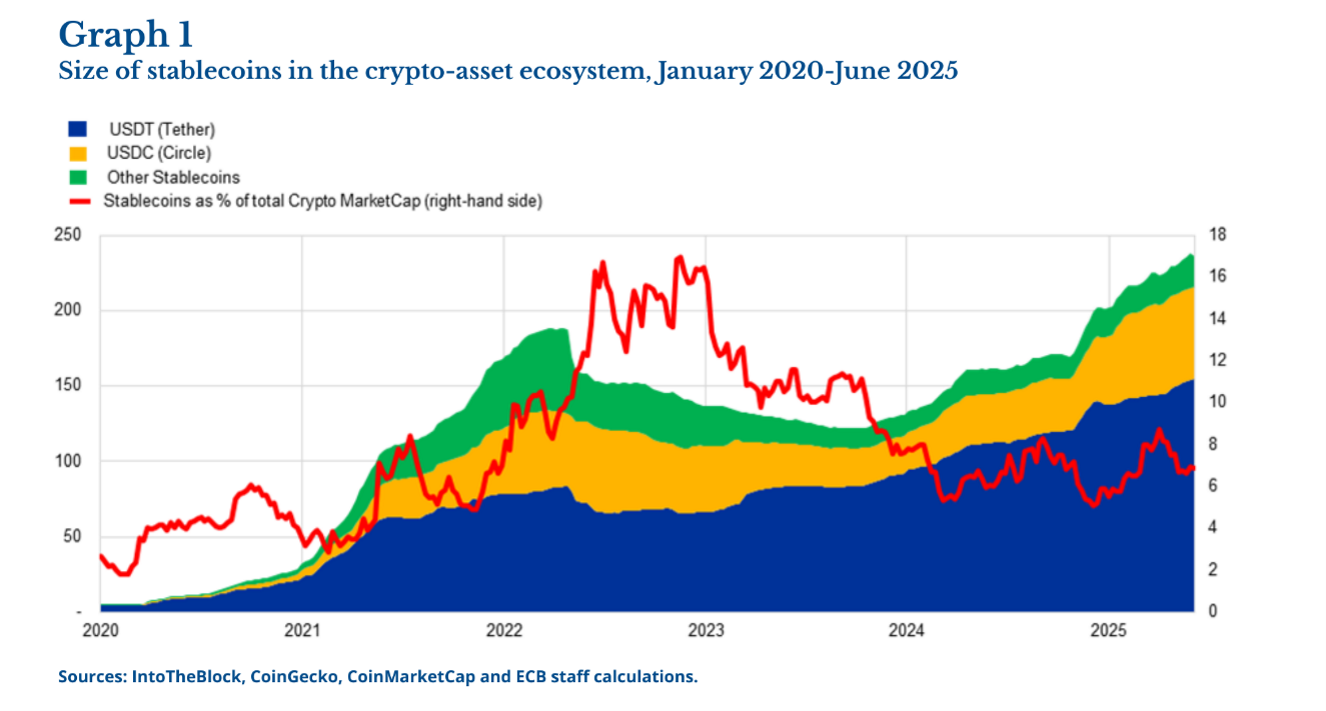

Stablecoins still make up a relatively small percentage of the overall crypto market, but have seen rapid growth in recent years. They have doubled in market capitalisation from $125bn in 2023, to c.$250bn in 2025, with 99 percent being pegged to the US dollar.

The US has moved fast to harness this growth. With other jurisdictions, caught flat footed, now trying to catch up.

Yet, Britain is falling behind. Despite action by the Treasury and the FCA to codify the UK’s own stablecoin and cryptoasset framework, momentum feels comparatively sluggish. Last week, in response to GENIUS Act, the EU hastened its plan for a central bank digital currency (CBDC): the digital euro. The UK’s response: still in consultation.

The Chancellor has made it no secret that she wants a “big bang on growth”. The ‘Big Bang’ of the 80s propelled London’s stock exchange into the future through tech and deregulation. 40 years on, it is once again, emerging tech—paired this time with a lack of regulation—that risks leaving our capital markets, and their core strengths, behind.

Competing Priorities: Growth vs. Stability

While the rest of the world moves to fight this out, UK policymakers remain divided on how to respond.

In some quarters, there is hesitancy to embrace the digital money revolution. Crypto’s image problem, often caricatured by the “crypto bro” or associated with illicit finance, has shaped wider scepticism. But on Threadneedle Street, crypto-scepticism is shaped by systemic concerns.

Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England, has been candid about his scepticism towards stablecoins or CBDC’s. On stablecoins, his concern is reflective of the competing priorities for government and the central bank. Last month, in his first letter as Chair of the Financial Stability Board, he identified the rise of stablecoins as a key risk to financial stability, and consistently argues that he doesn’t see any merit in developing a digital pound.

It’s fair to say that the Chancellor has signalled a willingness to embrace a fintech-driven future. The UK’s fintech sector, second only to the US in investment, has long argued that reforms must move faster. In a joint letter to the Chancellor, 30 industry leaders warned that innovation risked “evolving without UK participation.”

They see an opportunity to leverage the UK’s strength as the world’s leading foreign exchange hub: capturing just 10 percent of the $1trn stablecoin market could generate more than £1.4bn in new revenues, while also delivering “enhanced liquidity in UK capital markets, significant fintech investment inflows and job creation.”

The alternative is less appealing. Delaying reforms could leave the UK as a “rule-taker rather than a rule-maker.” At the same time, the Treasury has its own incentives, seeking to boost growth and strengthen the UK’s global competitiveness.

While this is certainly one of the Bank’s objectives, it’s a secondary one. The Bank’s statutory mandate, as set out in the Bank of England Act 1998, is to maintain price stability. Secondary to this is to support the government’s economic policy.

Bailey has warned that the rise of stablecoins threatened to take “money out of the banking system”— which in turn would weaken central bank’s ability to maintain price stability.

He is not alone in this scepticism. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), owned by 63 central banks, including the Bank of England, reached the same conclusion in its 2025 annual report. The BIS warned of a “major concern” that stablecoins could undermine monetary sovereignty, meaning the ability of a central bank to influence its monetary system.

Underlying this is a question of trust. Bailey stresses the importance of the ‘singleness of money’ — the idea that a pound in your account is always worth the same as a pound in mine. If stablecoins break that principle, trust in the financial system could unravel.

Bailey and the BIS agree on the risks. But stablecoins aren’t going anywhere. With the US pressing ahead and stablecoins acting as the gateway to wider crypto adoption, their influence is set to grow. Industry continues to press the case for embracing them. Yet without alignment between the Treasury and the Bank of England, Britain risks drifting while others set the course.

Turning Delay into Opportunity?

Britain will not be an early adopter of stablecoins; that much is clear. What’s the next available move? To be second adopters.

As Janine Hirt, CEO of Innovate Finance, points out, the UK has a “small window… to realise a second-mover advantage, learning lessons from first movers to deliver a regime that works.”

For an emerging technology, this may offer the UK a winning hand. There is considerable divergence between the leading jurisdictions: the US is pressing ahead with stablecoins, the EU is pursuing its digital euro, Japan is licensing bank-issued tokens, Singapore is trialling regulated pilots, and China is banning private coins in favour of its digital yuan. Lessons will be readily available, but to capitalise requires agility.

For Hirt and the industry, stablecoins represent the future. Hirt maintains that “as digital assets are set to form the foundation of the next wave of financial services”, therefore “the UK must act quickly and decisively to secure its seat at the table.”

The Bank of England plans to publish a consultation on stablecoins in the autumn, while the FCA will publish its draft rules in 2026. However, other jurisdictions are pressing their advantage and by 2026 it may be too late.

Britain needs to pave its own way. Whether that is stablecoins, a CBDC, or tokenised deposits, the UK must decide. Regulate stablecoins as financial infrastructure, pick a viable alternative, or risk the next era of capital markets being built elsewhere. If London wants to keep its crown as one of the world’s financial centres, indecision is no longer an option.