The Office for National Statistics (ONS), the UK’s statistics agency, has been in quiet crisis for some time. Senior leadership has resigned, and an independent review is steering its recovery.

Failure has left Britain’s long and winding road back to growth shrouded in fog, threatening to wreck the Autumn Budget. On such a journey, it isn’t the fog that kills you — it’s the unforeseen car at 100mph. All you can do is brace and hope to swerve in time. Britain now finds itself in that driver’s seat: steering blindfolded toward recovery.

The ONS produces the key economic indicators that policymakers rely on. But reliability problems mean that figures are often revised — sometimes dramatically, even erroneously. One flawed revision alone wiped £2 trillion off UK household wealth estimates. By all accounts, this was not an isolated incident.

These weaknesses would matter less if they were confined to the ONS. But unreliable inputs produce unreliable policy. Now, the core statistics that decide whether taxes will rise are, as Professor David Miles of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) explained, “no more than an educated guess, and maybe not even terribly educated.” Nonetheless, they exert significant influence on the bulk of Government policy.

From inactivity to productivity, the data is anything but exact. Failures at the ONS have baked error into the fiscal framework. Yet the Government has tried to operate with extraordinary precision. At the Spring Statement it restored ‘headroom’ to within a decimal place of £9.9bn. With such a slim margin, any deterioration risks the necessity of a policy response— fuelling uncertainty. But one revision from the ONS could blow a hole in the Governments plans.Planning is essential for good government — but for the Budget it looks increasingly impossible.

What happened to the ONS

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) sits at the centre of the ONS’s problems. As the Government’s key measure of employment and a critical input for the OBR’s forecasts, its reliability is vital. Yet during the pandemic, cracks widened into a full-blown collapse. Changes to the way the survey was conducted forced its withdrawal, revealing several weaknesses — two of them particularly damaging.

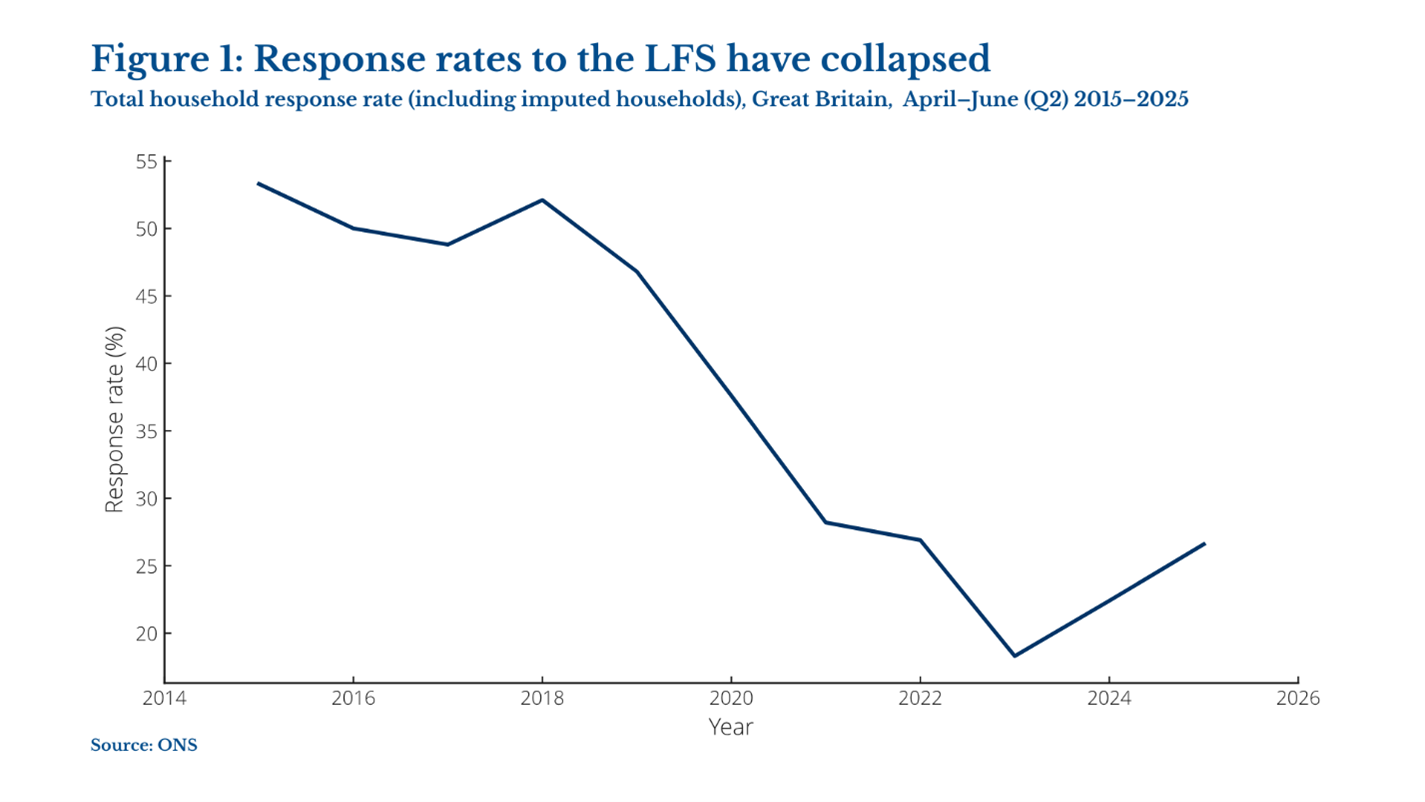

First, response rates collapsed from over 50 percent in 2015 to just 18 percent in 2023, making the survey volatile, unreliable and prone to large revisions.

As Xiaowei Xu of the IFS put it, the survey, therefore became “essentially useless.”

Second, the ONS changed how it conducted the survey. Traditionally reliant on in-person interviews, the LFS shifted during the pandemic to landline calls. This created new problems: landlines are rare among younger people, renters are less likely to have them, and unlike addresses, there is no comprehensive directory of phone numbers. The change may also have skewed the sample toward people more often at home.

To correct for this, the ONS adjusted response weights. But these fixes potentially introduced new biases that were hard to correct and likely skewed the demographics of respondents.

By October 2023, the LFS was withdrawn and downgraded from a trusted “national statistic” to an “experimental” one. Estimates of employment, unemployment, inactivity, now come with a warning stressing that “estimates of change should be treated with additional caution.”

Without reliable statistics, policymakers are left driving through the fog. Predictably, what follows is policy failure. This danger may have already played out in one of the country’s most urgent crises: the rapid rise in inactivity.

The Inactivity crisis that wasn’t?

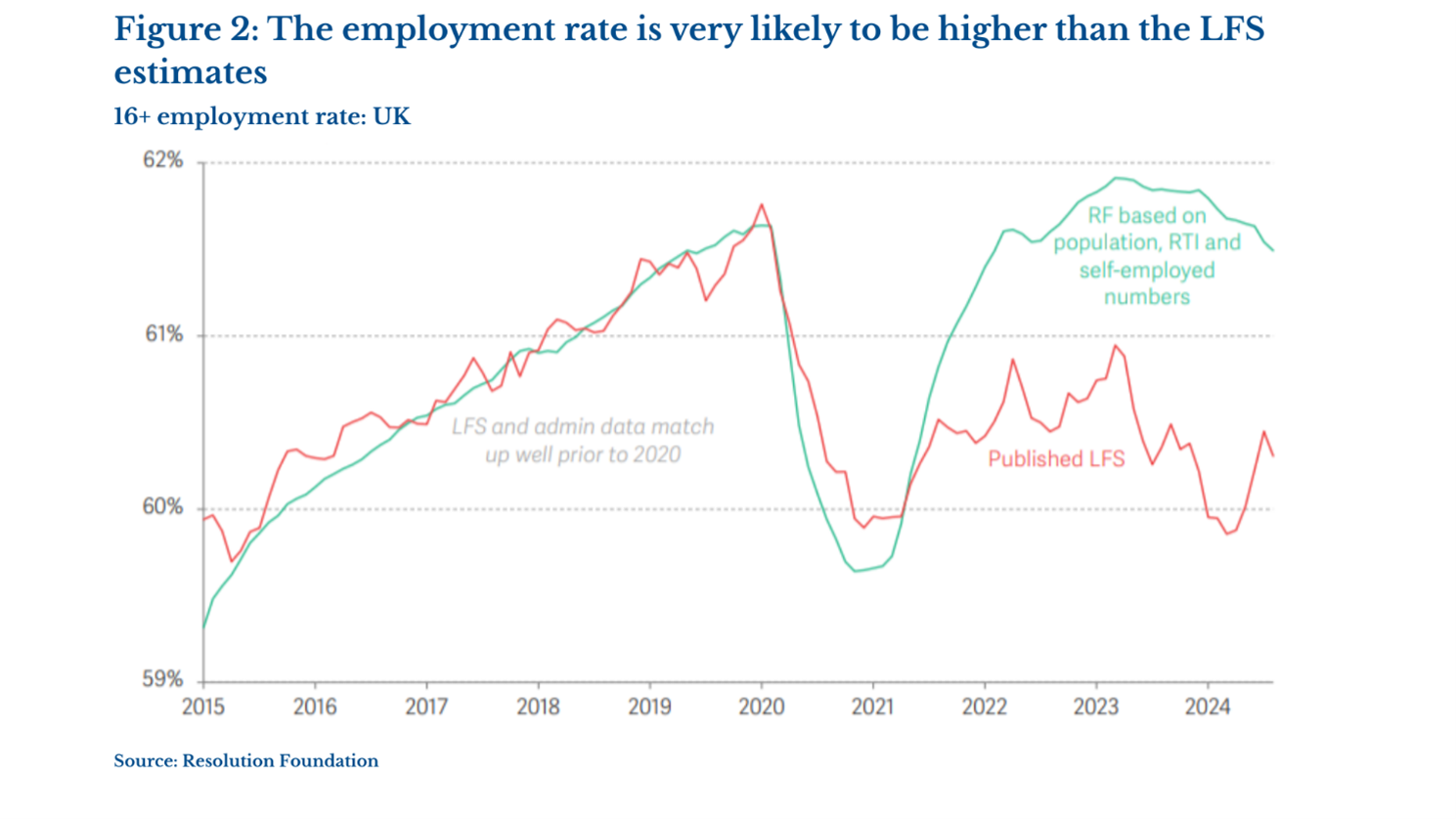

For context, the UK remains the only G7 country where economic inactivity is higher now than it was before the pandemic. Responding effectively to the crisis was and remains critical. Failure to do so risks rendering the welfare system unsustainable and worsening long-term employment outcomes. Yet Resolution Foundation research suggests ONS failures led to a serious misreading of the situation — undercounting employment growth while overstating inactivity.

As Figure 2 demonstrates, calculating the employment rate using HMRC admin data shows a sharp divergence with the LFS after 2020. While the two had tracked closely before, the Resolution Foundation contends LFS increasingly captured those more often at home — overstating inactivity by around 930,000 workers.

The ONS was quick to report the rise in inactivity in the wake of the pandemic. Ministers responded with interventions worth billions. Yet if the rise was little more than a data error, much of that effort (and money) risked being wasted — while other pressing challenges were neglected.

The Government is still grappling with inactivity. Its welfare reforms, aimed largely at stemming its rise, remain one of the most emotionally charged battlegrounds in British politics.

By the Government’s own admission, the reforms could push up to 250,000 people into relative poverty. 96 percent of those households have at least one member with a diagnosed disability and 50,000 are children. Of course, the fiscal sustainability of the welfare system is critical to ensuring long-term support for the most vulnerable. But if Ministers can’t even trust the data in front of them, how can any intervention be credible?

And that’s not the end of it. The Budget, too, is hostage to the same failures — where uncertainty itself can be fatal — especially for the markets and the credibility of the OBR’s forecasts.

Forecasting on shaky ground

Nowhere is this clearer than in productivity forecasting. Throughout the last decade or so, the UK has suffered anaemic productivity growth. As one of the drivers of broader growth, boosting productivity is essential to relieving fiscal pressure. But forecasts by the Bank of England and a chorus of others have consistently come in lower than the OBRs. Within the Bank, there is open scepticism about the OBR’s claims of a recovery.

The OBR are admittedly optimistic about the future of UK productivity yet have been mistaken in the past. Productivity is always hard to forecast, but as the Chair of the OBR, Richard Hughes admits, the “notorious issues” around the quality of the LFS, make for a “very cloudy picture” — making an already tough task much tougher.

Like the LFS, the ONS’ productivity estimates are “experimental”, hence the ONS’ advises to “expect revisions.” For them, these statistics “will potentially have a wider degree of uncertainty.” Worse yet, this uncertainty has increased post-pandemic, with the ONS already revising down its 2023 estimate from 0 percent annual growth to -0.4 percent.

Erratic data from the ONS means that the calculating productivity is “always a source of significant uncertainty” for the OBR’s forecasts. Taken literally, ONS data shows a 1 percent fall in productivity over the last year — a figure Hughes admits is hard to reconcile with reality. The end result is astonishing ambiguity on one of the UK’s key economic indicators and inputs to the OBRs forecast.

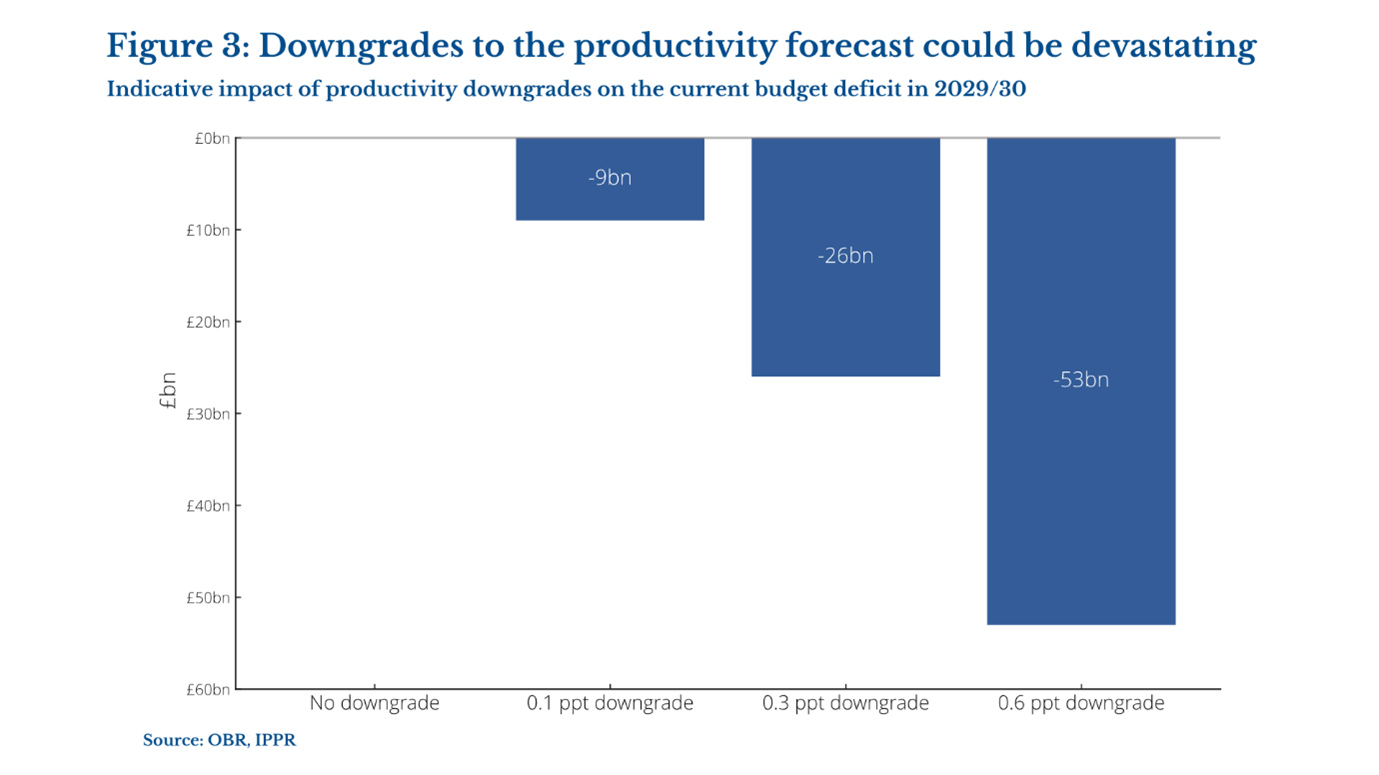

Fluctuating forecasts have the ability to derail the Government’s fiscal planning. A mere 0.1 percent downgrade in the forecasted rate of productivity costs the Government £9bn against their fiscal rules — equal to the entirety of the Government’s ‘headroom.’

The dilemma for the Treasury is that the OBR admits that its productivity forecasts are optimistic and faces pressure to downgrade them. Bringing them in line with the average independent forecast and restoring ‘headroom’ could cost £20bn— necessitating further tough decisions on tax and spending.

Ultimately, the consequences are bigger than the ONS itself. As Andrew Bailey lamented, it’s a “struggle to explain… why the British are particularly bad at this.” Nonetheless, the urgency to resolve the issues must be resolute.

Until trust in the UK’s data is restored, fiscal policy will remain vulnerable — not just to shocks in the real economy, but to flaws in the very statistics it relies upon. Failures at the ONS have baked in error, leaving Britain’s fiscal planning closer to guesswork than strategy.

For the Budget, that leaves the Government exposed to persistent surprise and uncertainty. It has already been reported that the OBR plans to downgrade its productivity forecast. By how much is still unknown. Until improvements arrive, Britain has no choice but to continue speeding down a foggy road, hopeful nothing lies ahead to crash its recovery.